the major documents of AMERICAN HISTORY

Among the great landmarks of the American story have been the charters, the United States Constitution (the “supreme law of the land”), constitutional amendments, laws,

and judicial opinions that have shaped the history of freedom and the development of our political and economic systems.

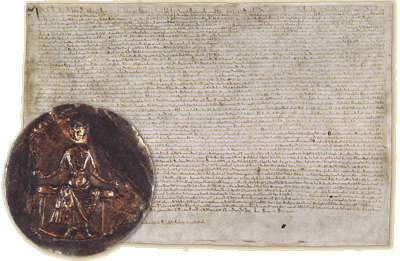

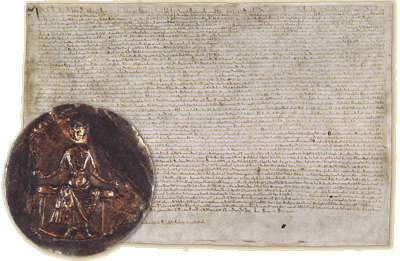

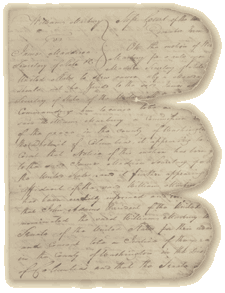

MAGNA CARTA 1215

[H]ere is a law which is above the King and which even he must not break. This reaffirmation of a supreme law and its expression in a general charter is the great work of Magna Carta; and this alone justifies the respect in which men have held it. —Winston Churchill, 1956

King John of England agreed in 1215 to the demands of his barons and authorized that handwritten copies of Magna Carta be prepared on parchment, affixed with his seal, and publicly read throughout the realm. Thus he bound not only himself but his “heirs, for ever” to grant “to all freemen of our kingdom” the rights and liberties the great charter described. With Magna Carta, King John placed himself and England's future sovereigns and magistrates within the rule of law.

When Englishmen left their homeland to establish colonies in the New World, they brought with them charters guaranteeing that they and their heirs would “have and enjoy all liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects.” When these American colonists raised arms against their mother country, they were fighting not for new freedoms but to preserve liberties that dated to the 13th century.

When representatives of the young republic of the United States gathered to draft a constitution, they turned to the legal system they knew and admired—English common law as evolved from Magna Carta. The conceptual debt to the great charter is particularly obvious: the American Constitution is “the Supreme Law of the Land,” just as the rights granted by Magna Carta were not to be arbitrarily canceled by subsequent English laws.

This heritage is most clearly apparent in the Bill of Rights. The Fifth Amendment guarantees “No person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” and the Sixth states, “[T]he accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury.” Written 575 years earlier, Magna Carta declares “No freeman shall be taken, imprisoned. . . , or in any other way destroyed . . . except by the lawful judgment of his peers, or by the law of the land. To no one will we sell, to none will we deny or delay, right or justice.”

In 1957 the American Bar Association acknowledged the debt American law and constitutionalism had to Magna Carta and English common law by erecting a monument at Runnymede, where King John signed the charter. Yet, as similar as Magna Carta and American protected liberties are, the basis for the liberties remain distinct. Magna Carta is a charter of ancient liberties guaranteed by a king to his subjects; the Constitution of the United States is the establishment of a government by and for “We the People.”

In 1957 the American Bar Association acknowledged the debt American law and constitutionalism had to Magna Carta and English common law by erecting a monument at Runnymede, where King John signed the charter. Yet, as similar as Magna Carta and American protected liberties are, the basis for the liberties remain distinct. Magna Carta is a charter of ancient liberties guaranteed by a king to his subjects; the Constitution of the United States is the establishment of a government by and for “We the People.”

To view this document and for more information visit www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured_documents/magna_carta/

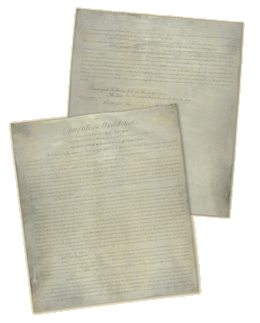

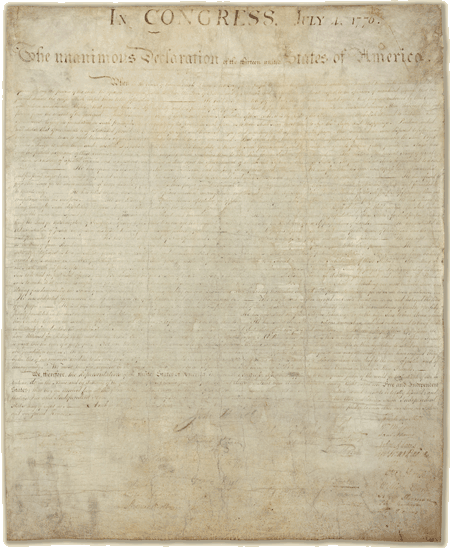

DECLARATION of

DECLARATION of

INDEPENDENCE 1776

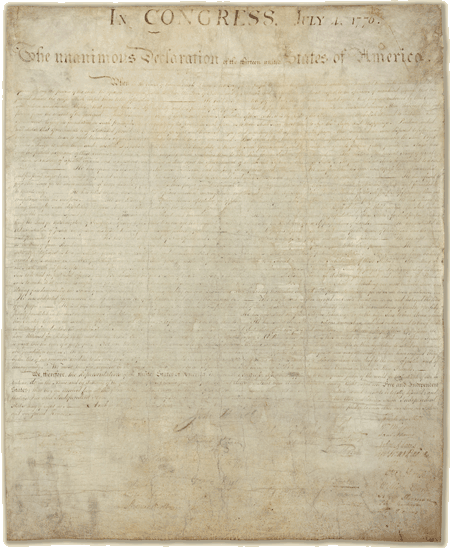

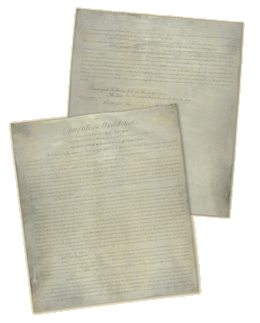

On June 10, 1776, with General Washington's army stationed in New York, the Continental Congress appointed a committee to draft a statement of independence for the American colonies. The committee included Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert R. Livingston, and Roger Sherman, with the actual writing delegated to Jefferson.

Jefferson drafted the statement between June 11 and 28, submitted drafts to Adams and Franklin who made some changes, and then presented the draft to the Congress. The congressional revision process took all of July 3 and most of July 4. Finally, on the afternoon of July 4, the Declaration of Independence was adopted.

Under the supervision of the Jefferson committee, the approved Declaration was printed on July 5 and a copy was attached to the “rough journal of the Continental Congress for July 4.” These printed copies were distributed to state assemblies, conventions, committees of safety, and commanding officers of the Continental troops.

On July 19, Congress ordered that the Declaration be “engrossed” on parchment with a new title, “the unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,” and “that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.” Engrossing is the process of copying an official document in a large hand.

On August 2, President of the Congress John Hancock signed the engrossed copy with a bold signature. The other delegates, following custom, signed beginning at the right with the signatures arranged by states from northernmost New Hampshire to southernmost Georgia. Although not all delegates were present on August 2, eventually 56 delegates signed the document.

To view this document and for more information visit www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration.html

Back to top

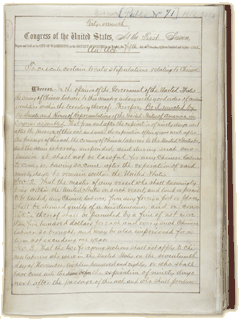

NORTHWEST ORDINANCE 1787

Adopted July 13, 1787, by the Second Continental Congress, the Northwest Ordinance chartered a government for the Northwest Territory, provided a method for admitting new states to the Union from the territory, and listed a bill of rights guaranteed in the territory. Following the principles outlined by Thomas Jefferson in the Ordinance of 1784, the authors of the Northwest Ordinance spelled out a plan that was subsequently used as the country expanded to the Pacific.

Adopted July 13, 1787, by the Second Continental Congress, the Northwest Ordinance chartered a government for the Northwest Territory, provided a method for admitting new states to the Union from the territory, and listed a bill of rights guaranteed in the territory. Following the principles outlined by Thomas Jefferson in the Ordinance of 1784, the authors of the Northwest Ordinance spelled out a plan that was subsequently used as the country expanded to the Pacific.

The following three principal provisions were ordained in the document: (1) a division of the Northwest Territory into “not less than three nor more than five States”; (2) a three-stage method for admitting a new state to the Union—with a congressionally appointed governor, secretary, and three judges to rule in the first phase; an elected assembly and one nonvoting delegate to Congress to be elected in the second phase, when the population of the territory reached “five thousand free male inhabitants of full age”; and a state constitution to be drafted and membership to the Union to be requested in the third phase when the population reached 60,000; and (3) a bill of rights protecting religious freedom, the right to a writ of habeas corpus, the benefit of trial by jury, and other individual rights. The ordinance also encouraged education and forbade slavery.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=8

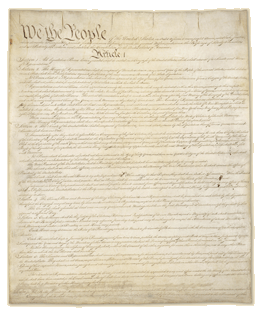

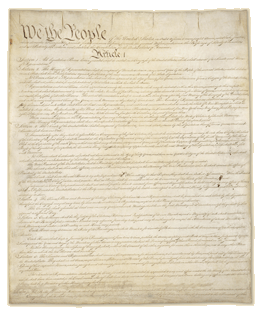

CONSTITUTION of the

UNITED STATES 1781

The Federal Convention convened in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia on May 14, 1787, to revise the Articles of Confederation. Because at first the delegations from only two states were present, the members adjourned from day to day until a quorum of seven states was obtained on May 25. Through discussion and debate it became clear by mid-June that, rather than amend the existing articles, the convention would draft an entirely new frame of government. All through the summer, in closed sessions, the delegates debated, and then redrafted the articles of the new Constitution. Among the chief points at issue were how much power to allow the central government, how many representatives in Congress to allow each state, and how these representatives should be elected—directly by the people or by the state legislators. The work of many minds, the Constitution stands as a model of cooperative statesmanship and the art of compromise.

The Federal Convention convened in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia on May 14, 1787, to revise the Articles of Confederation. Because at first the delegations from only two states were present, the members adjourned from day to day until a quorum of seven states was obtained on May 25. Through discussion and debate it became clear by mid-June that, rather than amend the existing articles, the convention would draft an entirely new frame of government. All through the summer, in closed sessions, the delegates debated, and then redrafted the articles of the new Constitution. Among the chief points at issue were how much power to allow the central government, how many representatives in Congress to allow each state, and how these representatives should be elected—directly by the people or by the state legislators. The work of many minds, the Constitution stands as a model of cooperative statesmanship and the art of compromise.

Article Three of the Constitution established the federal court system. The article reads:

Section 1

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services a Compensation which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

Section 2

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls; to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; to Controversies between two or more States; between a State and Citizens of another State; between Citizens of different States; between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed.

To view this document and for more information visit www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution.html

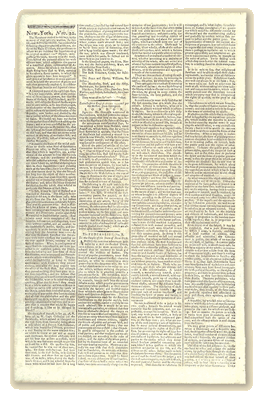

FEDERALIST PAPERS

NO. 10 AND NO. 51 1787-1788

The Federalist Papers were a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name “Publius,” primarily in two New York state newspapers of the time: The New York Packet and The Independent Journal.

The Federalist Papers were a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name “Publius,” primarily in two New York state newspapers of the time: The New York Packet and The Independent Journal.

The Papers were written to urge citizens of New York to support ratification of the proposed United States Constitution. The essays explain particular provisions of the Constitution in detail. It is for this reason, and because Hamilton and Madison were members of the Constitutional Convention, that The Federalist Papers are often used today to help understand the intentions of those drafting the Constitution.

With regard to judicial affairs, Federalist No. 78 famously states that “[t]o avoid an arbitrary discretion in the courts, it is indispensable that [judges] should be bound down by strict rules and precedents, which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them.” Federalist No. 80 discusses the necessity of extending judicial power to cases of equity and state immunity. Federalist No. 81 discusses the role of judicial review.

The essays seen here are Federalist No. 10 and Federalist No. 51. The former, written by James Madison, refuted the belief that it was impossible to extend a republican government over a large territory. It also discussed special interest groups. The latter emphasized the importance of checks and balances within a government.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=10

FEDERAL JUDICIARY ACT 1789

The founders of the new nation believed that the establishment of a national judiciary was one of their most important tasks. Yet Article III of the Constitution of the United States, the provision that deals with the judiciary branch of government, is markedly smaller than Articles I and II, which created the legislative and executive branches.

The generality of Article III of the Constitution raised questions that Congress had to address in the Judiciary Act of 1789. These questions had no easy answers, and the solutions to them were achieved politically. The First Congress decided that it could regulate the jurisdiction of all federal courts and, in the Judiciary Act of 1789, it established a limited jurisdiction for the district and circuit courts, gave the Supreme Court the original jurisdiction provided for in the Constitution, and granted the Court appellate jurisdiction in cases from the federal circuit courts and from the state courts where those courts' rulings had rejected federal claims. The decision to grant federal courts a jurisdiction more restrictive than that allowed by the Constitution represented Congress' recognition that the people of the United States would not find a full-blown federal court system palatable at that time.

For nearly all of the 19th century, the judicial system remained essentially as established by the Judiciary Act of 1789. Only after the country had expanded across the continent and been torn apart by civil war were major changes made. A separate tier of appellate circuit courts created in 1891 removed the burden of circuit riding from the shoulders of the Supreme Court justices, but otherwise left intact the judicial structure.

With minor adjustments, it is the same system that exists today. Congress has continued to build on the interpretation of the drafters of the first judiciary act in exercising a discretionary power to expand or restrict federalcourt jurisdiction. Although opinions on what constitutes the proper balance of federal and state concerns vary no less today than they did two centuries ago, the fact that today's federal court system closely resembles the one created in 1789 suggests that the First Congress performed its job admirably

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=12

Back to top

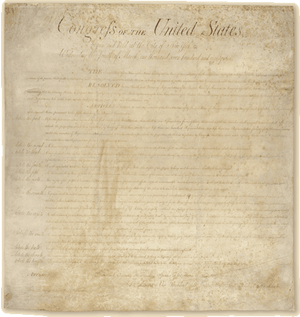

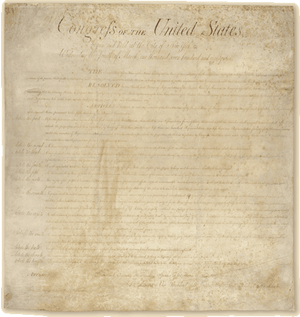

BILL OF RIGHTS 1791

During the debates on the adoption of the Constitution, its opponents repeatedly charged that the Constitution as drafted would open the way to tyranny by the central government. Fresh in their minds was the memory of the British violation of civil rights before and during the Revolution. They demanded a “bill of rights” that would spell out the protections of individual citizens. Several state conventions in their formal ratification of the Constitution asked for such amendments; others ratified the Constitution with the understanding that the amendments would be offered.

During the debates on the adoption of the Constitution, its opponents repeatedly charged that the Constitution as drafted would open the way to tyranny by the central government. Fresh in their minds was the memory of the British violation of civil rights before and during the Revolution. They demanded a “bill of rights” that would spell out the protections of individual citizens. Several state conventions in their formal ratification of the Constitution asked for such amendments; others ratified the Constitution with the understanding that the amendments would be offered.

On September 25, 1789, the First Congress of the United States therefore proposed to the state legislatures 12 amendments to the Constitution that met arguments most frequently advanced against it. Articles three to twelve, ratified December 15, 1791, by three-fourths of the state legislatures, constitute the first 10 amendments of the Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights. Article two concerning “varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives” was finally ratified on May 7, 1992, as the Twenty-seventh Amendment to the Constitution. The first article, which concerned the number of constituents for each Representative, was never ratified.

To view this document and for more information visit www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/bill_of_rights.html

ALIEN and SEDITION ACTS 1798

In 1798 the United States stood on the brink of war with France, its great ally during the Revolution a mere 20 years earlier. The Federalists believed that Democratic-Republican criticism of Federalist policies was disloyal and feared that aliens living in the United States would sympathize with the French during a war. As a result, a Federalist-controlled Congress passed four laws, known collectively as the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws raised the residency requirements for citizenship from 5 to 14 years, authorized the president to deport aliens; and permitted their arrest, imprisonment, and deportation during wartime. The Sedition Act made it a crime for American citizens to “print, utter, or publish . . . any false, scandalous, and malicious writing” about the government.

The laws were directed against Democratic-Republicans, the party typically favored by new citizens. The only journalists prosecuted under the Sedition Act were editors of Democratic- Republican newspapers. Sedition Act trials, along with the Senate's use of its contempt powers to suppress dissent, set off a firestorm of criticism against the Federalists and contributed to their defeat in the election of 1800, after which the acts were repealed or allowed to expire. The controversies surrounding them, however, provided for some of the first tests of the limits of freedom of speech and the press.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=16

Marbury v. Madison 1808

Marbury v. Madison 1808

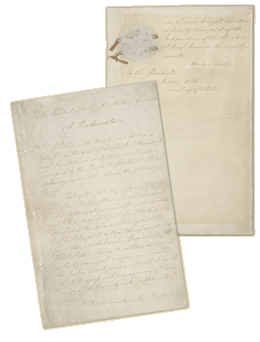

Outgoing President John Adams had issued William Marbury a commission as justice of the peace, but the new secretary of state, James Madison, refused to deliver it. Marbury then sued to obtain it. With his decision in Marbury v. Madison, Chief Justice John Marshall established the principle of judicial review, an important addition to the system of “checks and balances” created to prevent any one branch of the federal government from becoming too powerful. The document shown here bears the marks of the Capitol fire of 1898.

“;A Law repugnant to the Constitution is void.” With these words written by Chief Justice Marshall, the Supreme Court for the first time declared unconstitutional a law passed by Congress and signed by the president. Nothing in the Constitution gave the Court this specific power. Marshall, however, believed that the Supreme Court should have a role equal to those of the other two branches of government.

When James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay wrote a defense of the Constitution in The Federalist, they explained their judgment that a strong national government must have built-in restraints: “You must first enable government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.” The writers of the Constitution had given the executive and legislative branches powers that would limit each other as well as the judiciary branch. The Constitution gave Congress the power to impeach and remove officials, including judges or the president himself. The president was given the veto power to restrain Congress and the authority to appoint members of the Supreme Court with the advice and consent of the Senate. In this intricate system, the role of the Supreme Court had not been defined. It therefore fell to a strong chief justice like Marshall to complete the triangular structure of checks and balances by establishing the principle of judicial review. Although no other law was declared unconstitutional until the Dred Scott decision of 1857, the role of the Supreme Court to invalidate federal and state laws that are contrary to the Constitution has never been seriously challenged.

The often-praised wisdom of the authors of the Constitution consisted largely of their restraint. They resisted the temptation to write too many specifics into the basic document. They contented themselves with establishing a framework of government that included safeguards against the abuse of power. When the Marshall decision Marbury v. Madison completed the system of checks and balances, the United States had a government in which laws could be enacted, interpreted, and executed to meet challenging circumstances.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=19

Back to top

Gibbons v. Ogden 1824

The State of New York passed a law giving Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston a monopoly on steamboat traffic on the Hudson Bay, “navigating all boats that might be propelled by steam, on all waters within the territory, or jurisdiction of the State, for the term of twenty years.” Fulton and Livingston issued permits and seized boats that operated without their endorsement.

Aaron Ogden had a license from the State of New York to navigate between New York City and the New Jersey Shore. Ogden found himself competing with Thomas Gibbons, who had been given permission to use the waterways by the federal government. After the State of New York denied Gibbons access to Hudson's Bay, he sued Ogden.

The case went to the Supreme Court and Chief Justice John Marshall's opinion carried out the clear original intent of the Constitution to have Congress, not the states, regulate interstate commerce. In this decision, Chief Justice Marshall's Court ruled that Congress has the power to “regulate commerce” and that federal law takes precedence over state laws. Marshall's decision sustained the nationalist definition of federal power and ruled that Congress could constitutionally regulate many activities that affected interstate commerce.

In the wake of this decision, the federal government, empowered by the Constitution's commerce clause, increasingly exercised its authority by legislation and judicial decision over the whole range of the nation's economic life.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=24

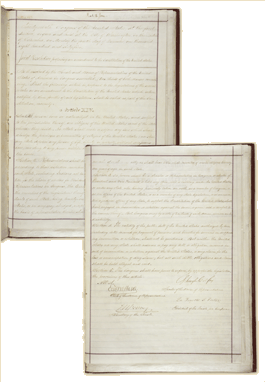

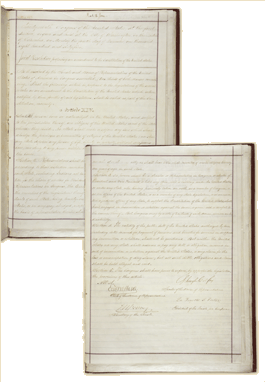

TREATY WITH THE WALLA WALLA, CAYUSE and UMATILLA 1855

In 1855 representatives of the federal government and the chiefs of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla tribes signed a treaty in which the tribes gave up, or ceded, to the United States more than 6.4 million acres in what is now northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington. The treaty designated a parcel of land as the Umatilla Indian Reservation that the tribes would retain as a permanent homeland. The treaty was signed on June 9, 1855, ratified by Congress on March 8, 1859, and proclaimed on April 11, 1859.

The Treaty of 1855 established “the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed places, in common with the citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary buildings for curing them; together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing horses and cattle upon open and unclaimed land.” In the treaty, the tribes reserved the rights to fish, hunt, and gather traditional foods and medicines throughout the ceded lands. The tribes still protect and exercise those rights within the 6.4 million acres of ceded land in what is now northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington.

It is important to understand that the U.S. Government and the Treaty did not “give” the tribal people those rights to fish, hunt, and gather foods and medicines. Rather, they are rights that the tribes have had and exercised since time immemorial. In the Treaty, tribal signatories “reserved” those rights to ensure that future generations would be able to maintain and exercise tribal traditions and customs.

Because of those reserved treaty rights in the 6.4 million acres, the tribes maintain a keen interest and involvement in the activities that occur in that area. United States District Judges Robert Belloni (Sohappy v. Smith, 302 F. Supp. 899 [D. Or. 1969]) and George Boldt (United States v. Washington, 384 F. Supp. 312 [W.D. Wash. 1974]) reaffirmed the federal government's guarantee to northwest Indians the right to fish “at all usual and accustomed places.” Since the 1970s, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has been asked to balance Indian fishing rights with environmental and other concerns in a series of cases that continues today.

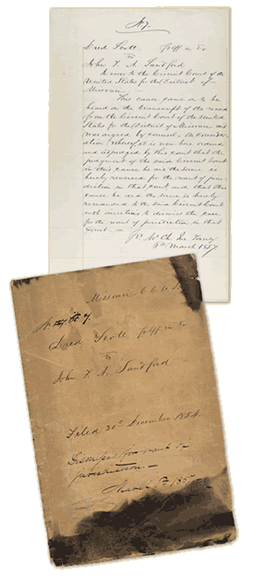

Dred Scott v. Sanford 1857

In 1846 a slave named Dred Scott and his wife, Harriet, sued for their freedom in a St. Louis city court. The odds were in their favor. They had lived with their owner, an army surgeon, at Fort Snelling, then in the free Territory of Wisconsin. The Scotts' freedom could be established on the grounds that they had been held in bondage for extended periods in a free territory and were then returned to a slave state. Courts had ruled this way in the past. However, what appeared to be a straightforward lawsuit between two private parties became an 11-year legal struggle that culminated in one of the most notorious decisions ever issued by the United States Supreme Court.

On its way to the Supreme Court, the Dred Scott case grew in scope and significance as slavery became the single most explosive issue in American politics. By the time the case reached the high court, it had come to have enormous political implications for the entire nation.

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney read the majority opinion of the Court, which stated that slaves were not citizens of the United States and, therefore, could not expect any protection from the federal government or the courts. The opinion also stated that Congress had no authority to ban slavery from a federal territory. This decision moved the nation a step closer to civil war.

The decision in Scott v. Sanford, considered by legal scholars to be the worst ever rendered by the Supreme Court, was overturned by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution, which abolished slavery and declared all persons born in the United States to be citizens of the United States.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=29

Back to top

EMANCIPATION

PROCLAMATION 1863

Initially, the Civil War between North and South was fought by the North to prevent the secession of the Southern states and preserve the Union. Even though sectional conflicts over slavery had been a major cause of the war, ending slavery was not a goal of the war. That changed on September 22, 1862, when President Abraham Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which stated that slaves in those states or parts of states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be declared free. One hundred days later, with the rebellion unabated, the president issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring “that all person held as slaves” within the rebellious areas “are, and henceforward shall be, free.”

Lincoln's bold step to change the goals of the war was a military measure and came just a few days after the Union's victory in the Battle of Antietam. With this Proclamation he hoped to inspire all blacks, and slaves in the Confederacy in particular, to support the Union cause and to keep England and France from giving political recognition and military aid to the Confederacy. Because it was a military measure, however, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal Border States. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Union control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it did fundamentally transform the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.

From the first days of the Civil War, slaves had acted to secure their own liberty. The Emancipation Proclamation confirmed their insistence that the war for the Union must become a war for freedom. It added moral force to the Union cause and strengthened the Union both militarily and politically. As a milestone along the road to slavery's final destruction, the Emancipation Proclamation has assumed a place among the great documents of human freedom.

To view this document and for more information visit www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured_documents/emancipation_proclamation/

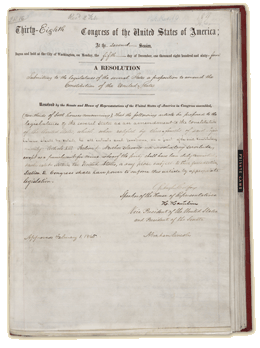

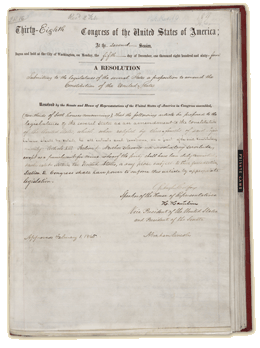

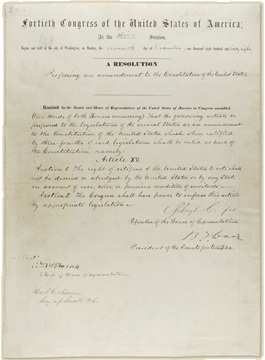

THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT to the United States Constitution: ABOLITION OF SLAVERY 1865

The Thirteenth Amendment, which formally abolished slavery in the United States, passed the Senate on April 8, 1864, and the House on January 31, 1865. On February 1, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress submitting the proposed amendment to the state legislatures. The necessary number of states ratified it by December 6, 1865. The 13th amendment to the United States Constitution provides that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

In 1863 President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Nonetheless, the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation. Lincoln recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation would have to be followed by a constitutional amendment to guarantee the abolishment of slavery.

The Thirteenth Amendment was passed at the end of the Civil War before the Southern states had been restored to the Union and should have easily passed the Congress. Although the Senate passed it in April 1864, the House did not. At that point, Lincoln took an active role to ensure passage through Congress. He insisted that passage of the Thirteenth Amendment be added to the Republican Party platform for the upcoming Presidential elections. His efforts met with success when the House passed the bill in January 1865 with a vote of 119–56.

With the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment, the United States found a final constitutional solution to the issue of slavery. The 13th amendment is one in the trio of Civil War amendments, including the Fourteenth and Fifteenth, that greatly expanded the civil rights of Americans.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=40

Back to top

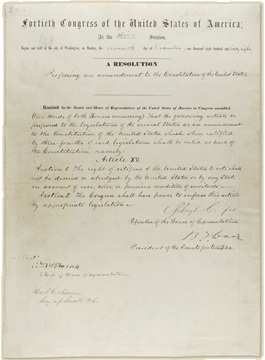

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

to the United States Constitution: CIVIL RIGHTS 1868

Following the Civil War, Congress submitted to the states three constitutional amendments as part of its Reconstruction program to guarantee equal civil and legal rights to black citizens. The major provision of the Fourteenth Amendment was to grant citizenship to “All persons born or naturalized in the United States,” thereby granting citizenship to former slaves. An equally important provision was the statement “nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The right to due process of law and equal protection of the law now applied to both the federal and state governments. On June 16, 1866, the House Joint Resolution proposing the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution was submitted to the states. On July 28, 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment, in a certificate of the secretary of state, was declared ratified by the necessary 28 of the 37 states, and became part of the supreme law of the land.

While some in Congress intended that the Fourteenth Amendment would extend the federal Bill of Rights to the states, it failed to protect the rights of black citizens. One legacy of Reconstruction was the determined struggle of black and white citizens to make the promise of the 14th amendment a reality. Citizens petitioned and initiated court cases, Congress enacted legislation, and the executive branch attempted to enforce measures that would guard all citizens' rights. While these citizens did not succeed in empowering the Fourteenth Amendment during the latter part of the 19th century, they effectively articulated arguments and offered dissenting opinions that would be the basis for change in the 20th century.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=43

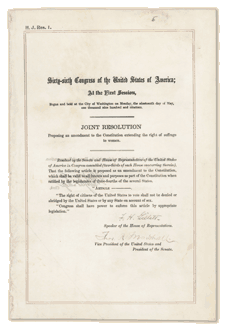

FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT to the United States Constitution: VOTING RIGHTS 1870

To former abolitionists and to the Radical Republicans in Congress who fashioned Reconstruction after the Civil War, the Fifteenth Amendment, enacted in 1870, appeared to signify the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans. Set free by the Thirteenth Amendment, with citizenship guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, black males were given the vote by the Fifteenth Amendment. From that point on, the freedmen were generally expected to fend for themselves. In retrospect, it can be seen that the Fifteenth Amendment was only the beginning of a struggle for equality that would continue for more than a century before African Americans could begin to participate more fully in American public and civic life.

To former abolitionists and to the Radical Republicans in Congress who fashioned Reconstruction after the Civil War, the Fifteenth Amendment, enacted in 1870, appeared to signify the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans. Set free by the Thirteenth Amendment, with citizenship guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, black males were given the vote by the Fifteenth Amendment. From that point on, the freedmen were generally expected to fend for themselves. In retrospect, it can be seen that the Fifteenth Amendment was only the beginning of a struggle for equality that would continue for more than a century before African Americans could begin to participate more fully in American public and civic life.

African Americans exercised the franchise and held office in many Southern states through the 1880s, but in the early 1890s, steps were taken to ensure subsequent “white supremacy.”Literacy tests for the vote, “grandfather clauses” excluding from the franchise all whose ancestors had not voted in the 1860s, and other devices to disenfranchise African Americans were written into the constitutions of former Confederate states. Social and economic segregation were added to black America's loss of political power.

In 1896 the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson legalized “separate but equal” facilities for the races. For more than 50 years after that, the overwhelming majority of African-American citizens were reduced to second-class citizenship under the “Jim Crow” segregation system. During that time, African Americans sought to secure their rights and improve their position through organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the National Urban League and through the individual efforts of reformers like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and A. Philip Randolph.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=44

Back to top

CHINESE EXCLUSION ACTS 1882

CHINESE EXCLUSION ACTS 1882

In the spring of 1882, Congress passed and President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act. This act provided a 10-year moratorium on Chinese labor immigration. For the first time, federal law proscribed entry of an ethnic working group on the premise that it endangered the good order of certain localities.

The Chinese Exclusion Act required the few non-laborers who sought entry to obtain certification from the Chinese government that they were qualified to immigrate. But this group found it increasingly difficult to prove that they were not laborers because the 1882 act defined excludables as “skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining.” Thus, very few Chinese could enter the country under the 1882 law.

The 1882 exclusion act also placed new requirements on Chinese who had already entered the country. If they left the United States, they had to obtain certifications to re-enter. Congress, moreover, refused state and federal courts the right to grant citizenship to Chinese resident aliens, although these courts could still deport them.

When the exclusion act expired in 1892, Congress extended it for 10 years in the form of the Geary Act. This extension, made permanent in 1902, added restrictions by requiring each Chinese resident to register and obtain a certificate of residence. Without a certificate, he or she faced deportation.

The Geary Act regulated Chinese immigration until the 1920s. With increased postwar immigration, Congress adopted new means for regulation: quotas and requirements pertaining to national origin. By this time, anti-Chinese agitation had quieted. In 1943 Congress repealed all the exclusion acts, leaving a yearly limit of 105 Chinese, and gave foreign-born Chinese the right to seek naturalization. The so-called national origin system, with various modifications, lasted until Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1965. Effective July 1, 1968, a limit of 170,000 immigrants from outside the Western Hemisphere could enter the United States, with a maximum of 20,000 from any one country. Skill and the need for political asylum determined admission. The Immigration Act of 1990 provided the most comprehensive change in legal immigration since 1965. The act established a “flexible” worldwide cap on family-based, employment-based, and diversity immigrant visas. The act further provides that visas for any single foreign state in these categories may not exceed 7 percent of the total available.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=47

Plessy v. Ferguson 1896

During the era of Reconstruction, black Americans' political rights were affirmed by three constitutional amendments and numerous laws passed by Congress. Racial discrimination was attacked on a particularly broad front by the Civil Rights Act of 1875. This legislation made it a crime for an individual to deny “the full and equal enjoyment of any of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement; subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law, and applicable alike to citizens of every race and color.”

In 1883, the Supreme Court struck down the 1875 act, ruling that the Fourteenth Amendment did not give Congress authority to prevent discrimination by private individuals. Victims of racial discrimination were told to seek relief not from the federal government, but from the states. Unfortunately, state governments were passing legislation that codified inequality between the races. Laws requiring the establishment of separate schools for children of each race were most common; however, segregation was soon extended to encompass most public and semi-public facilities.

Beginning with passage of an 1887 Florida law, states began to require that railroads furnish separate accommodations for each race. These measures were unpopular with the railway companies that bore the expense of adding segregated cars. Segregation of the railroads was even more objectionable to black citizens, who saw it as a further step toward the total repudiation of three constitutional amendments. When such a bill was proposed before the Louisiana legislature in 1890, the articulate black community of New Orleans protested vigorously. Nonetheless, despite the presence of 16 black legislators in the state assembly, the law was passed. It required either separate passenger coaches or partitioned coaches to provide segregated accommodations for each race. Passengers were required to sit in the appropriate areas or face a $25 fine or a 20-day jail sentence. Black nurses attending white children, however, were permitted to ride in white compartments.

Beginning with passage of an 1887 Florida law, states began to require that railroads furnish separate accommodations for each race. These measures were unpopular with the railway companies that bore the expense of adding segregated cars. Segregation of the railroads was even more objectionable to black citizens, who saw it as a further step toward the total repudiation of three constitutional amendments. When such a bill was proposed before the Louisiana legislature in 1890, the articulate black community of New Orleans protested vigorously. Nonetheless, despite the presence of 16 black legislators in the state assembly, the law was passed. It required either separate passenger coaches or partitioned coaches to provide segregated accommodations for each race. Passengers were required to sit in the appropriate areas or face a $25 fine or a 20-day jail sentence. Black nurses attending white children, however, were permitted to ride in white compartments.

In 1891, a group of concerned young black men of New Orleans formed the “Citizens' Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law.” They raised money and engaged Albion W. Tourgée, a prominent Radical Republican author and politician, as their lawyer. On May 15, 1892, the Louisiana State Supreme Court decided in favor of the Pullman Company's claim that the law was unconstitutional as it applied to interstate travel. Encouraged, the committee decided to press a test case on intrastate travel. With the cooperation of the East Louisiana Railroad, on June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy, a mulatto who was seven-eighths white, seated himself in a white compartment, was challenged by the conductor, and was arrested and charged with violating the state law. In the Criminal District Court for the Parish of Orleans, Tourgée argued that the law requiring “separate but equal accommodations” was unconstitutional. When Judge John H. Ferguson ruled against him, Plessy applied to the Louisiana Supreme Court for a writ of prohibition and certiorari. Although the court upheld the state law, it granted Plessy's petition for a writ of error that would enable him to appeal the case to the United States Supreme Court.

In a powerful dissent, conservative Kentuckian John Marshall Harlan wrote:

”I am of the opinion that the statute of Louisiana is inconsistent with the personal liberties of citizens, white and black, in that State, and hostile to both the spirit and the letter of the Constitution of the United States. If laws of like character should be enacted in the several States of the Union, the effect would be in the highest degree mischievous. Slavery as an institution tolerated by law would, it is true, have disappeared from our country, but there would remain a power in the States, by sinister legislation, to interfere with the blessings of freedom; to regulate civil rights common to all citizens, upon the basis of race; and to place in a condition of legal inferiority a large body of American citizens, now constituting a part of the political community, called the people of the United States, for whom and by whom, through representatives, our government is administrated. Such a system is inconsistent with the guarantee given by the constitution to each state of a republican form of government, and may be stricken down by congressional action, or by the courts in the discharge of their solemn duty to maintain the supreme law of the land, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.”

Indeed, it was not until the Supreme Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas and congressional civil-rights acts of the 1950s and 1960s that systematic segregation under state law was ended. In the wake of those federal actions, many states amended or rewrote their state constitutions to conform to the spirit of the Fourteenth Amendment. But for Homer Plessy the remedies came too late.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=52

Back to top

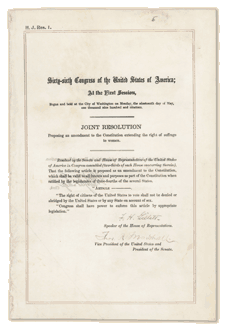

NINETEENTH AMENDMENT to the United States Constitution: WOMEN'S RIGHT TO VOTE 1920

NINETEENTH AMENDMENT to the United States Constitution: WOMEN'S RIGHT TO VOTE 1920

The Nineteenth Amendment guarantees all American women the right to vote. Achieving this milestone required a lengthy and difficult struggle; victory took decades of agitation and protest. Beginning in the mid-19th century, several generations of woman suffrage supporters lectured, wrote, marched, lobbied, and practiced civil disobedience to achieve what many Americans considered a radical change of the Constitution. Few early supporters lived to see final victory in 1920.

Between 1878, when the amendment was first introduced in Congress, and August 18, 1920, when it was ratified, champions of voting rights for women worked tirelessly, but strategies for achieving their goal varied. Some pursued a strategy of passing suffrage acts in each state. Nine western states—Oregon among them (where Abigail Scott Duniway led the cause)—adopted woman suffrage legislation by 1912. Others challenged male-only voting laws in the courts. Militant suffragists used tactics such as parades, silent vigils, and hunger strikes. Often supporters met fierce resistance. Opponents heckled, jailed, and sometimes physically abused them.

By 1916, almost all of the major suffrage organizations were united behind the goal of a constitutional amendment. When New York adopted woman suffrage in 1917 and President Woodrow Wilson changed his position to support an amendment in 1918, the political balance began to shift.

By 1916, almost all of the major suffrage organizations were united behind the goal of a constitutional amendment. When New York adopted woman suffrage in 1917 and President Woodrow Wilson changed his position to support an amendment in 1918, the political balance began to shift.

On May 21, 1919, the House of Representatives passed the amendment. Two weeks later, the Senate followed. When Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the amendment on August 18, 1920, it passed its final hurdle of obtaining the agreement of three-fourths of the states. (Oregon had granted women the vote eight years earlier.) Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby certified the ratification on August 26, 1920, changing the face of the American electorate forever.

To view this document and for more information visit www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured_documents/amendment_19/

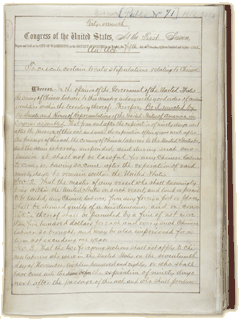

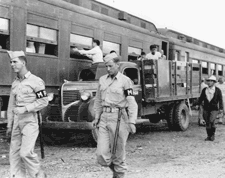

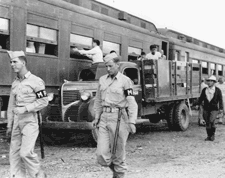

EXECUTIVE ORDER 9066 resulting in the RELOCATION OF JAPANESE AMERICANS 1942

Between 1861 and 1940, approximately 275,000 Japanese immigrated to Hawaii and the mainland United States, the majority arriving between 1898 and 1924, when quotas were adopted that ended Asian immigration. Many worked in Hawaiian sugarcane fields as contract laborers. After their contracts expired, a small number remained and opened up shops. Other Japanese immigrants settled on the West Coast of mainland United States, cultivating marginal farmlands and fruit orchards, fishing, and operating small businesses. Their efforts yielded impressive results. Japanese Americans controlled less than 4 percent of California's farmland in 1940, but they produced more than 10 percent of the total value of the state's farm resources.

Between 1861 and 1940, approximately 275,000 Japanese immigrated to Hawaii and the mainland United States, the majority arriving between 1898 and 1924, when quotas were adopted that ended Asian immigration. Many worked in Hawaiian sugarcane fields as contract laborers. After their contracts expired, a small number remained and opened up shops. Other Japanese immigrants settled on the West Coast of mainland United States, cultivating marginal farmlands and fruit orchards, fishing, and operating small businesses. Their efforts yielded impressive results. Japanese Americans controlled less than 4 percent of California's farmland in 1940, but they produced more than 10 percent of the total value of the state's farm resources.

As was the case with other immigrant groups, Japanese Americans settled in ethnic neighborhoods and established their own schools, houses of worship, and economic and cultural institutions. Ethnic concentration was further increased by real estate agents who would not sell properties to Japanese Americans outside of existing Japanese enclaves and by a 1913 act passed by the California Assembly restricting land ownership to those eligible to be citizens. In 1922 the U.S. Supreme Court, in Ozawa v. United States, upheld the government's right to deny U.S. citizenship to Japanese immigrants.

Envy over economic success combined with distrust over cultural separateness and long-standing anti-Asian racism turned into disaster when the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Lobbyists from western states, many representing competing economic interests or nativist groups, pressured Congress and the President to remove persons of Japanese descent from the west coast, both foreign born (issei – meaning “first generation” of Japanese in the U.S.) and American citizens (nisei – the second generation of Japanese in America, U.S. citizens by birthright.) During Congressional committee hearings, Department of Justice representatives raised constitutional and ethical objections, so the U.S. Army carried out the task. The West Coast was divided into military zones. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing exclusion. Congress implemented the order on March 21, 1942, by passing Public Law 503.

After encouraging voluntary evacuation of the areas, the Western Defense Command began involuntary removal and detention of West Coast residents of Japanese ancestry. In the next 6 months, approximately 122,000 men, women, and children were moved to assembly centers. They were then evacuated to and confined in isolated, fenced, and guarded relocation centers, known as internment camps. The 10 relocation sites were in remote areas in 6 western states and Arkansas: Heart Mountain in Wyoming, Tule Lake and Manzanar in California, Topaz in Utah, Poston and Gila River in Arizona, Granada in Colorado, Minidoka in Idaho, and Jerome and Rowher in Arkansas.

Nearly 70,000 of the evacuees were American citizens. The government made no charges against them, nor could they appeal their incarceration. All lost personal liberties; most lost homes and property as well. Although several Japanese Americans challenged the government's actions in court cases, the Supreme Court upheld their legality. Nisei were nevertheless encouraged to serve in the armed forces, and some were also drafted. Altogether, more than 30,000 Japanese Americans served with distinction during World War II in segregated units.

For many years after the war, various individuals and groups sought compensation for the internees. The speed of the evacuation forced many homeowners and businessmen to sell out quickly; total property loss is estimated at $1.3 billion, and net income loss calculated at $2.7 billion. The Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, with amendments in 1951 and 1965, provided token payments for some property losses. More serious efforts to make amends took place in the early 1980s, when the congressionally established Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians held investigations and made recommendations. As a result, several bills were introduced in Congress from 1984 until 1988, when Public Law 100-383, which acknowledged the injustice of the internment, apologized for it, and provided for restitution, was passed.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=74

Back to top

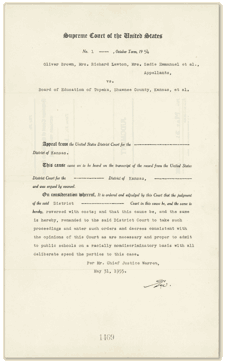

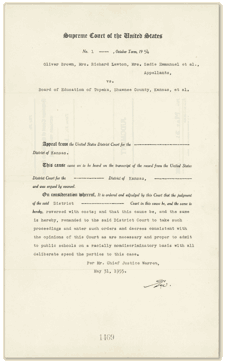

Brown v. Board of Education 1954

On May 17, 1954, United States Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Statesanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the “separate but equal” precedent set by the Supreme Court nearly 60 years earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement during the decade of the 1950s.

Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine just how the ruling would be implemented. Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II, instructing the states to begin desegregation plans “with all deliberate speed.”

Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine just how the ruling would be implemented. Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II, instructing the states to begin desegregation plans “with all deliberate speed.”

Despite two unanimous decisions and careful, if vague, wording, there was considerable resistance to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. In addition to the obvious disapproving segregationists were some constitutional scholars who felt that the decision went against legal tradition by relying heavily on data supplied by social scientists rather than precedent or established law. Supporters of judicial restraint believed the Court had overstepped its constitutional powers by essentially writing new law.

Minority groups and members of the civil rights movement were buoyed by the Brown decision even without specific directions for implementation. Proponents of judicial activism believed the Supreme Court had appropriately used its position to adapt the basis of the Constitution to address new problems in new times. The Warren Court stayed this course for the next 15 years, deciding cases that significantly affected not only race relations, but also the administration of criminal justice, the operation of the political process, and the separation of church and state.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=87

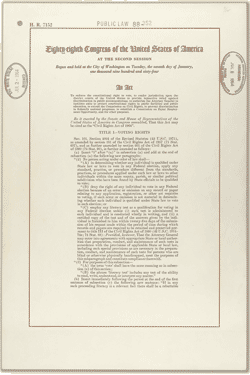

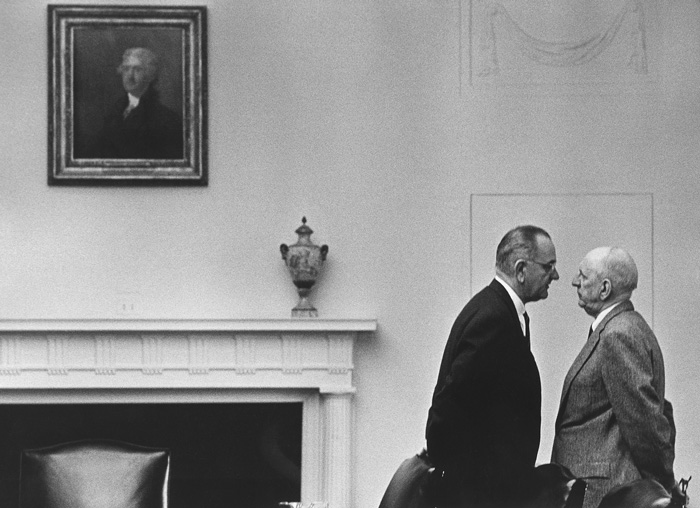

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT 1964

In a nationally televised address on June 6, 1963, President John F. Kennedy urged the nation to take action toward guaranteeing equal treatment of every American regardless of race. Soon after, Kennedy proposed that Congress consider civil-rights legislation that would address voting rights, public accommodations, school desegregation, nondiscrimination in federally assisted programs, and more.

Despite Kennedy's assassination in November 1963, his proposal culminated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson just a few hours after Senate approval on July 2, 1964. The act outlawed segregation in businesses such as theaters, restaurants, and hotels. It banned discriminatory practices in employment and ended segregation in public places such as swimming pools, libraries, and public schools.

Passage of the act was not easy. House opposition bottled up the bill in the House Rules Committee. In the Senate, opponents attempted to talk the bill to death in a filibuster. In early 1964, House supporters overcame the Rules Committee obstacle by threatening to send the bill to the floor without committee approval. The Senate filibuster was overcome through the floor leadership of Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, the persuasion of President Johnson, and the efforts of Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois, who persuaded Republicans to support the bill.

To view this document and for more information visit www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=97

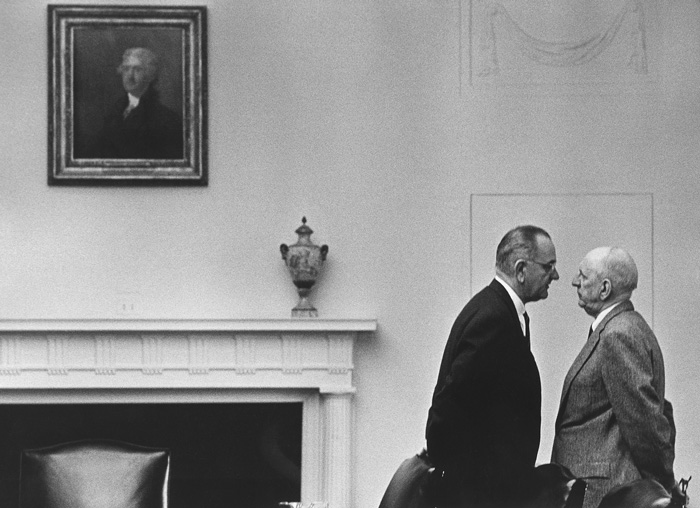

President Lyndon B. Johnson with Senator Richard Russell, December 7, 1963 National Archives

President Lyndon B. Johnson with Senator Richard Russell, December 7, 1963 National Archives

Back to top

In 1957 the American Bar Association acknowledged the debt American law and constitutionalism had to Magna Carta and English common law by erecting a monument at Runnymede, where King John signed the charter. Yet, as similar as Magna Carta and American protected liberties are, the basis for the liberties remain distinct. Magna Carta is a charter of ancient liberties guaranteed by a king to his subjects; the Constitution of the United States is the establishment of a government by and for “We the People.”

In 1957 the American Bar Association acknowledged the debt American law and constitutionalism had to Magna Carta and English common law by erecting a monument at Runnymede, where King John signed the charter. Yet, as similar as Magna Carta and American protected liberties are, the basis for the liberties remain distinct. Magna Carta is a charter of ancient liberties guaranteed by a king to his subjects; the Constitution of the United States is the establishment of a government by and for “We the People.”

Adopted July 13, 1787, by the Second Continental Congress, the Northwest Ordinance chartered a government for the Northwest Territory, provided a method for admitting new states to the Union from the territory, and listed a bill of rights guaranteed in the territory. Following the principles outlined by Thomas Jefferson in the Ordinance of 1784, the authors of the Northwest Ordinance spelled out a plan that was subsequently used as the country expanded to the Pacific.

Adopted July 13, 1787, by the Second Continental Congress, the Northwest Ordinance chartered a government for the Northwest Territory, provided a method for admitting new states to the Union from the territory, and listed a bill of rights guaranteed in the territory. Following the principles outlined by Thomas Jefferson in the Ordinance of 1784, the authors of the Northwest Ordinance spelled out a plan that was subsequently used as the country expanded to the Pacific.  The Federal Convention convened in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia on May 14, 1787, to revise the Articles of Confederation. Because at first the delegations from only two states were present, the members adjourned from day to day until a quorum of seven states was obtained on May 25. Through discussion and debate it became clear by mid-June that, rather than amend the existing articles, the convention would draft an entirely new frame of government. All through the summer, in closed sessions, the delegates debated, and then redrafted the articles of the new Constitution. Among the chief points at issue were how much power to allow the central government, how many representatives in Congress to allow each state, and how these representatives should be elected—directly by the people or by the state legislators. The work of many minds, the Constitution stands as a model of cooperative statesmanship and the art of compromise.

The Federal Convention convened in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia on May 14, 1787, to revise the Articles of Confederation. Because at first the delegations from only two states were present, the members adjourned from day to day until a quorum of seven states was obtained on May 25. Through discussion and debate it became clear by mid-June that, rather than amend the existing articles, the convention would draft an entirely new frame of government. All through the summer, in closed sessions, the delegates debated, and then redrafted the articles of the new Constitution. Among the chief points at issue were how much power to allow the central government, how many representatives in Congress to allow each state, and how these representatives should be elected—directly by the people or by the state legislators. The work of many minds, the Constitution stands as a model of cooperative statesmanship and the art of compromise.  The Federalist Papers were a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name “Publius,” primarily in two New York state newspapers of the time: The New York Packet and The Independent Journal.

The Federalist Papers were a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name “Publius,” primarily in two New York state newspapers of the time: The New York Packet and The Independent Journal.

During the debates on the adoption of the Constitution, its opponents repeatedly charged that the Constitution as drafted would open the way to tyranny by the central government. Fresh in their minds was the memory of the British violation of civil rights before and during the Revolution. They demanded a “bill of rights” that would spell out the protections of individual citizens. Several state conventions in their formal ratification of the Constitution asked for such amendments; others ratified the Constitution with the understanding that the amendments would be offered.

During the debates on the adoption of the Constitution, its opponents repeatedly charged that the Constitution as drafted would open the way to tyranny by the central government. Fresh in their minds was the memory of the British violation of civil rights before and during the Revolution. They demanded a “bill of rights” that would spell out the protections of individual citizens. Several state conventions in their formal ratification of the Constitution asked for such amendments; others ratified the Constitution with the understanding that the amendments would be offered.

To former abolitionists and to the Radical Republicans in Congress who fashioned Reconstruction after the Civil War, the Fifteenth Amendment, enacted in 1870, appeared to signify the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans. Set free by the Thirteenth Amendment, with citizenship guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, black males were given the vote by the Fifteenth Amendment. From that point on, the freedmen were generally expected to fend for themselves. In retrospect, it can be seen that the Fifteenth Amendment was only the beginning of a struggle for equality that would continue for more than a century before African Americans could begin to participate more fully in American public and civic life.

To former abolitionists and to the Radical Republicans in Congress who fashioned Reconstruction after the Civil War, the Fifteenth Amendment, enacted in 1870, appeared to signify the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans. Set free by the Thirteenth Amendment, with citizenship guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, black males were given the vote by the Fifteenth Amendment. From that point on, the freedmen were generally expected to fend for themselves. In retrospect, it can be seen that the Fifteenth Amendment was only the beginning of a struggle for equality that would continue for more than a century before African Americans could begin to participate more fully in American public and civic life.

Beginning with passage of an 1887 Florida law, states began to require that railroads furnish separate accommodations for each race. These measures were unpopular with the railway companies that bore the expense of adding segregated cars. Segregation of the railroads was even more objectionable to black citizens, who saw it as a further step toward the total repudiation of three constitutional amendments. When such a bill was proposed before the Louisiana legislature in 1890, the articulate black community of New Orleans protested vigorously. Nonetheless, despite the presence of 16 black legislators in the state assembly, the law was passed. It required either separate passenger coaches or partitioned coaches to provide segregated accommodations for each race. Passengers were required to sit in the appropriate areas or face a $25 fine or a 20-day jail sentence. Black nurses attending white children, however, were permitted to ride in white compartments.

Beginning with passage of an 1887 Florida law, states began to require that railroads furnish separate accommodations for each race. These measures were unpopular with the railway companies that bore the expense of adding segregated cars. Segregation of the railroads was even more objectionable to black citizens, who saw it as a further step toward the total repudiation of three constitutional amendments. When such a bill was proposed before the Louisiana legislature in 1890, the articulate black community of New Orleans protested vigorously. Nonetheless, despite the presence of 16 black legislators in the state assembly, the law was passed. It required either separate passenger coaches or partitioned coaches to provide segregated accommodations for each race. Passengers were required to sit in the appropriate areas or face a $25 fine or a 20-day jail sentence. Black nurses attending white children, however, were permitted to ride in white compartments.

By 1916, almost all of the major suffrage organizations were united behind the goal of a constitutional amendment. When New York adopted woman suffrage in 1917 and President Woodrow Wilson changed his position to support an amendment in 1918, the political balance began to shift.

By 1916, almost all of the major suffrage organizations were united behind the goal of a constitutional amendment. When New York adopted woman suffrage in 1917 and President Woodrow Wilson changed his position to support an amendment in 1918, the political balance began to shift.  Between 1861 and 1940, approximately 275,000 Japanese immigrated to Hawaii and the mainland United States, the majority arriving between 1898 and 1924, when quotas were adopted that ended Asian immigration. Many worked in Hawaiian sugarcane fields as contract laborers. After their contracts expired, a small number remained and opened up shops. Other Japanese immigrants settled on the West Coast of mainland United States, cultivating marginal farmlands and fruit orchards, fishing, and operating small businesses. Their efforts yielded impressive results. Japanese Americans controlled less than 4 percent of California's farmland in 1940, but they produced more than 10 percent of the total value of the state's farm resources.

Between 1861 and 1940, approximately 275,000 Japanese immigrated to Hawaii and the mainland United States, the majority arriving between 1898 and 1924, when quotas were adopted that ended Asian immigration. Many worked in Hawaiian sugarcane fields as contract laborers. After their contracts expired, a small number remained and opened up shops. Other Japanese immigrants settled on the West Coast of mainland United States, cultivating marginal farmlands and fruit orchards, fishing, and operating small businesses. Their efforts yielded impressive results. Japanese Americans controlled less than 4 percent of California's farmland in 1940, but they produced more than 10 percent of the total value of the state's farm resources.  Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine just how the ruling would be implemented. Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II, instructing the states to begin desegregation plans “with all deliberate speed.”

Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine just how the ruling would be implemented. Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II, instructing the states to begin desegregation plans “with all deliberate speed.”