Pioneer Courthouse

GALLERIES

1942-1946

Japanese-American Internment During World War II

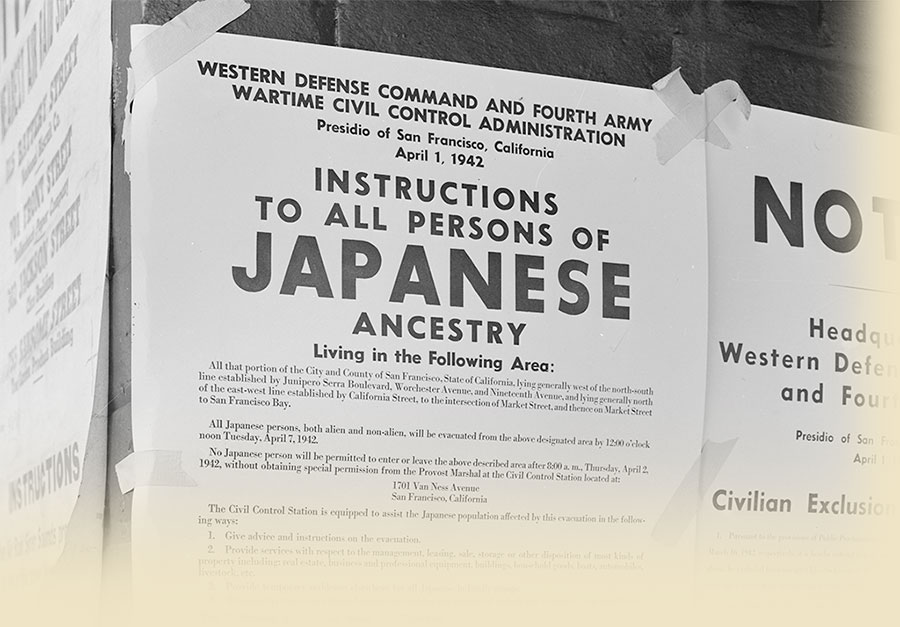

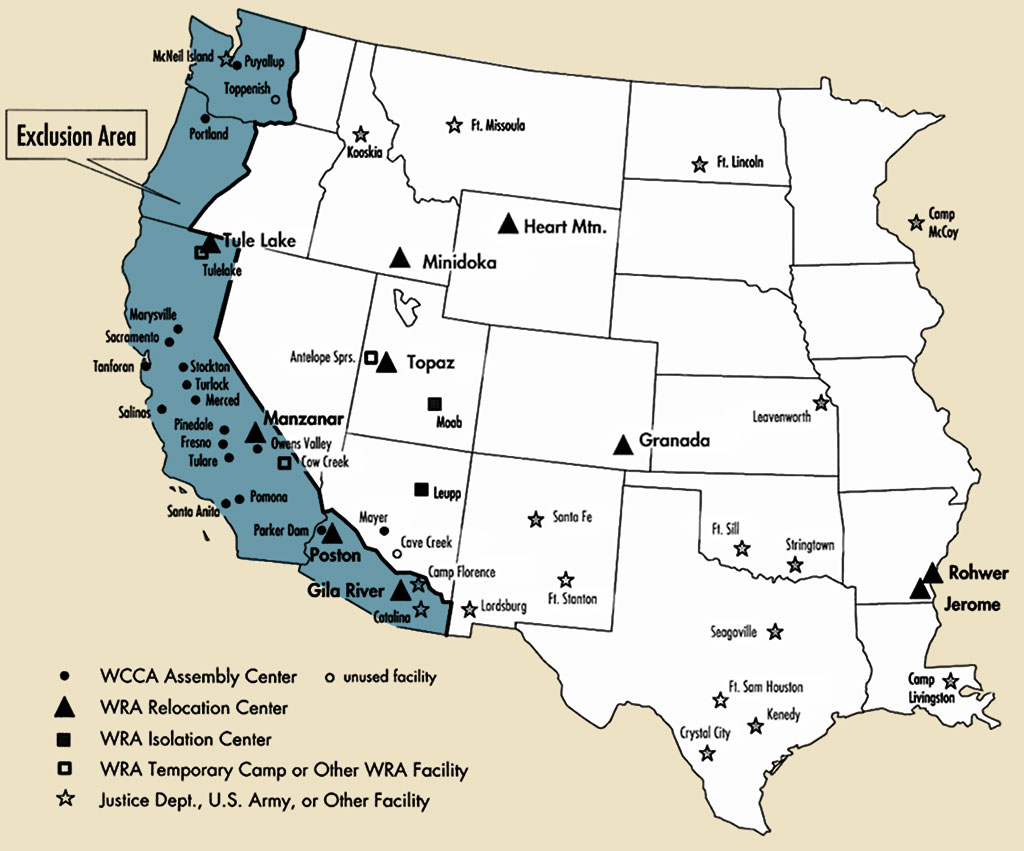

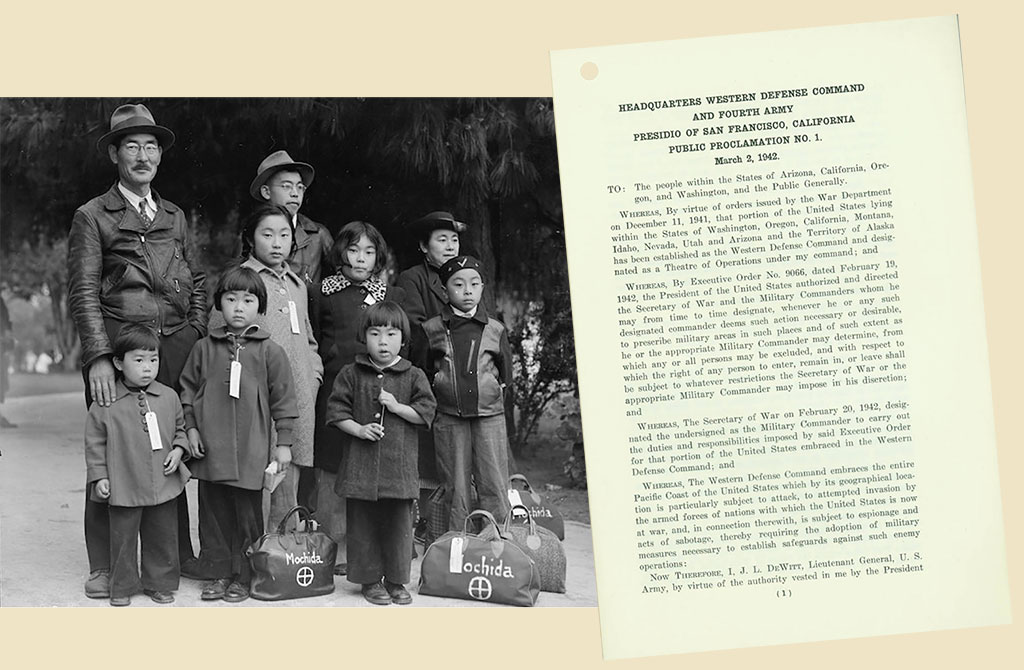

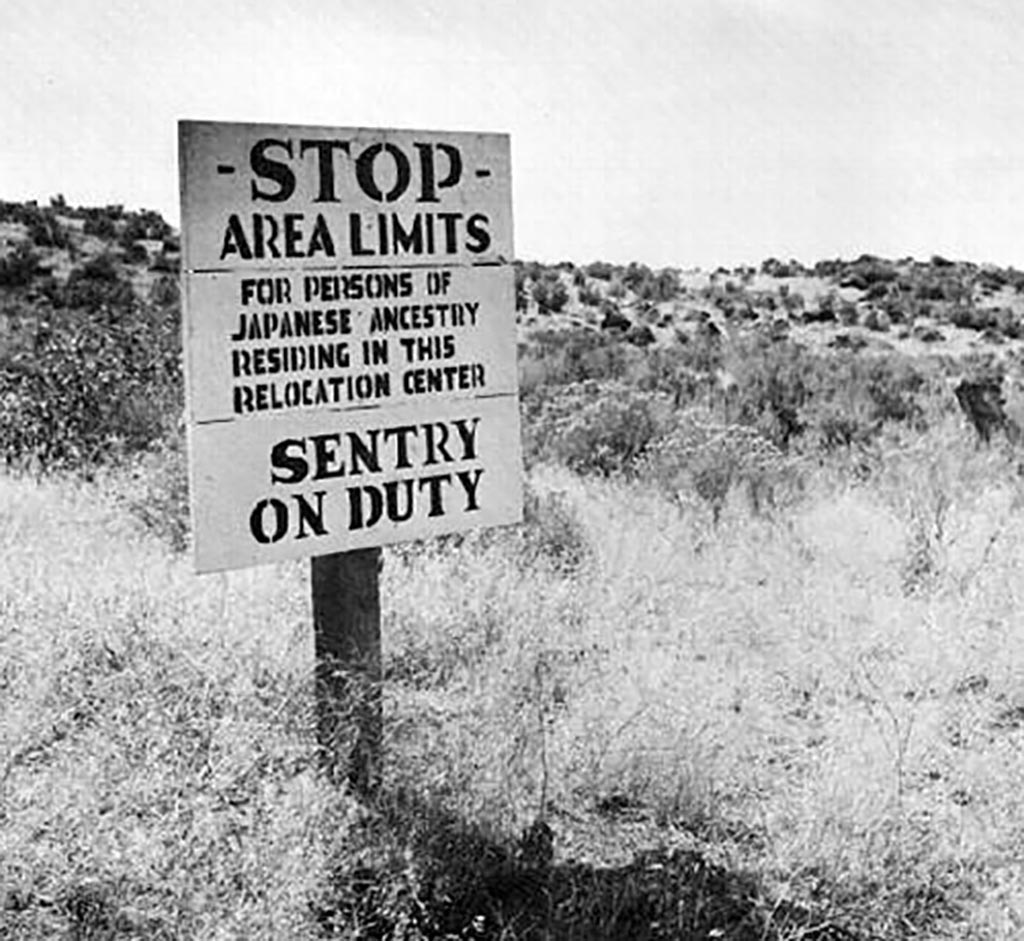

In the wake of the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the War Department to create military areas from which any or all Americans might be excluded, and to provide for the necessary transport, lodging, and feeding of persons displaced from such areas. On March 2, 1942, the U.S. Army Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, commander of the Western Defense Command, issued Public Proclamation No. 1, demarcating western military areas and the exclusion zones therein, and directing any “Japanese, German, or Italian aliens” and any person of Japanese descent to inform the U.S. Postal Service of any changes of residence. Further military areas and zones were demarcated in Public Proclamation No. 2.

On March 24, 1942, Western Defense Command began issuing Civilian Exclusion orders, commanding that “all persons of Japanese ancestry, including aliens and non-aliens” report to designated assembly points. With the issuance of Civilian Restrictive Order No. 1 on May 19, 1942, Japanese Americans were forced to move into relocation camps.

Bancroft Library

Bancroft Library

Upon the implementation of Executive Order 9066, approximately 122,000 Japanese Americans along the West Coast were rounded up and sent to internment camps.

Photo by Dorothea Lange

Photo by Dorothea Lange

Photo by Dorothea Lange

Photo by Dorothea Lange

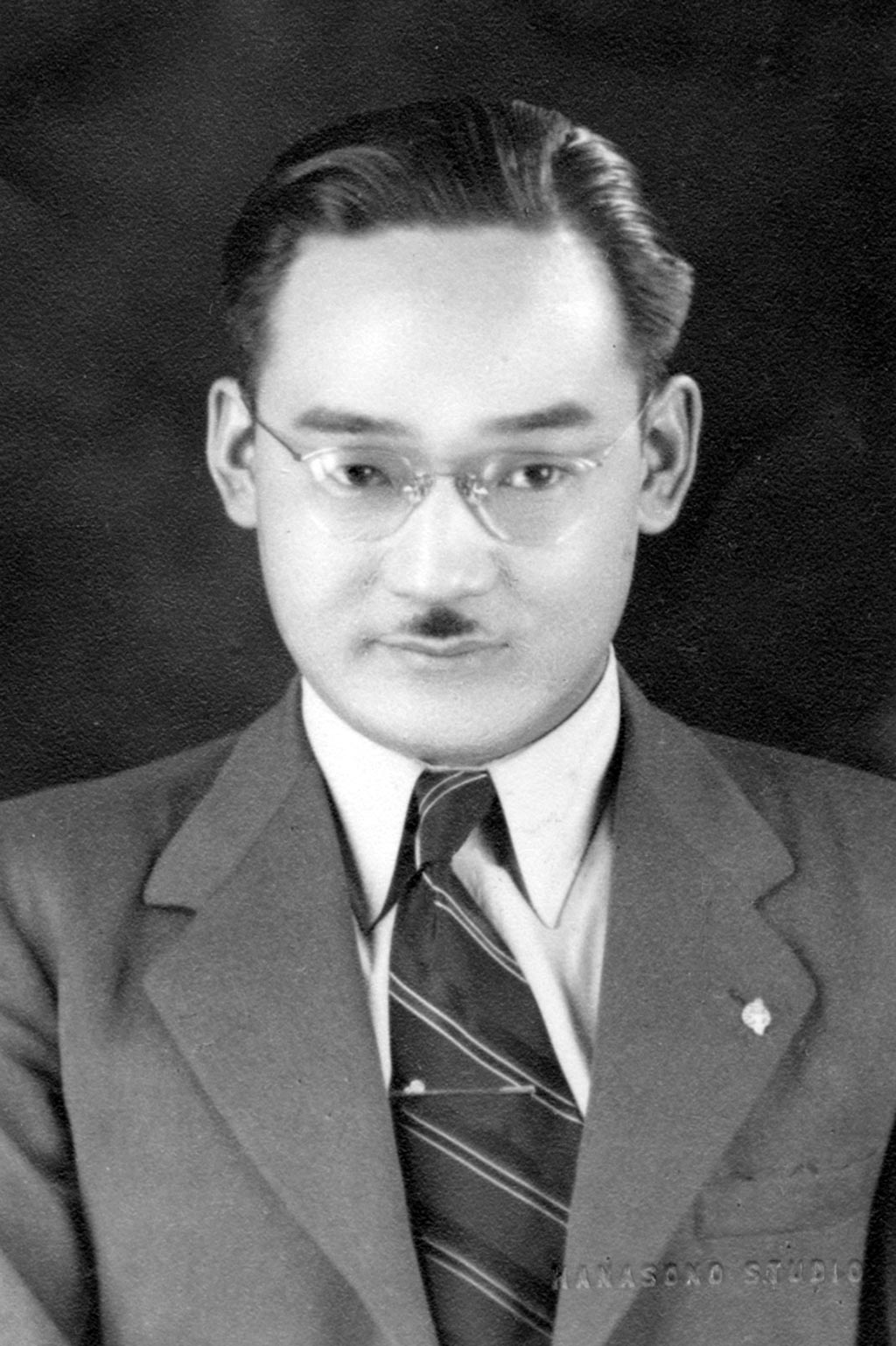

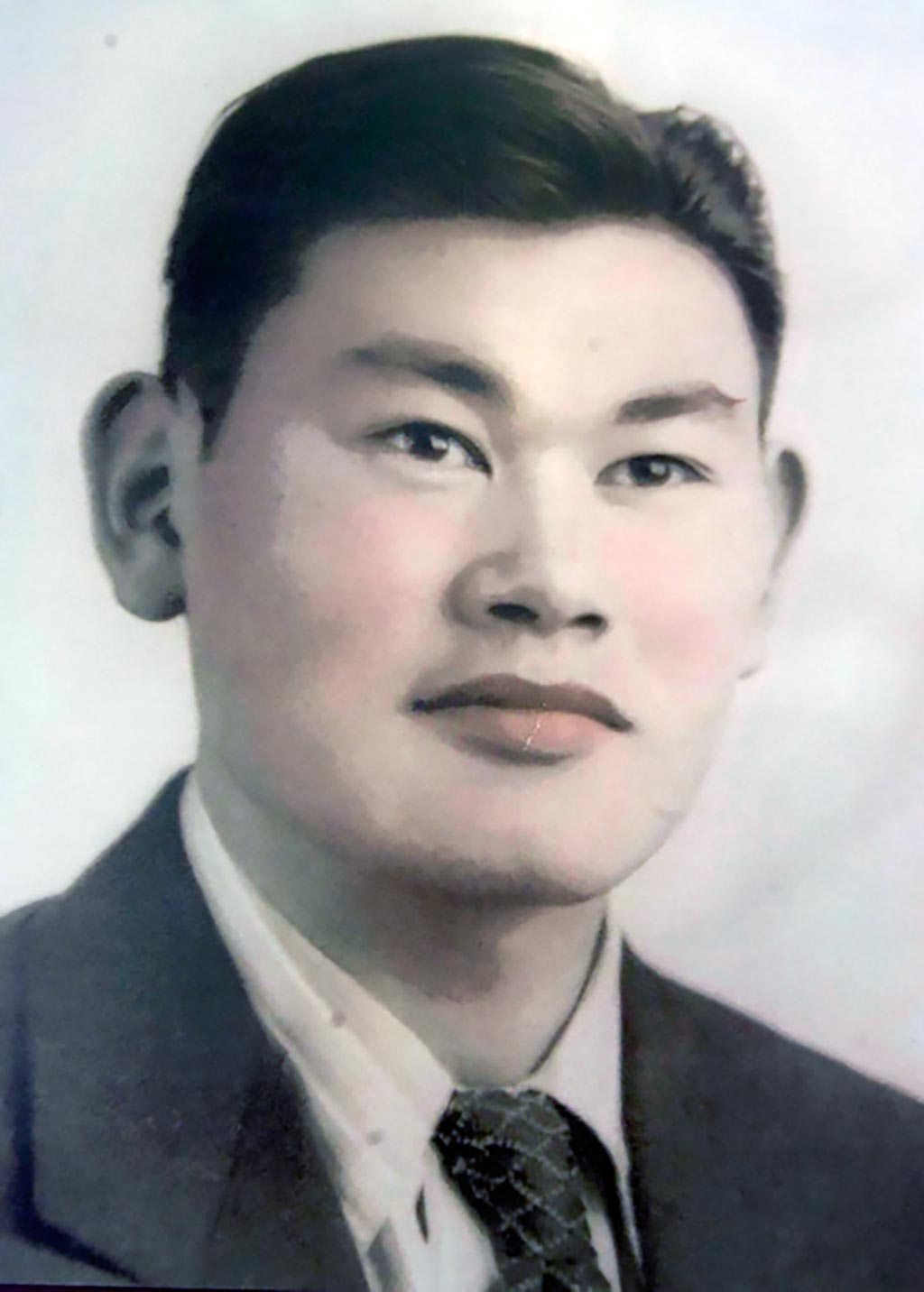

Minoru Yasui

Minoru Yasui

Fred Korematsu

Fred Korematsu

Minoru Yasui, a graduate of the University of Oregon Law School, objected to the order and broke the curfew imposed on Japanese Americans. He went to trial and was ultimately stripped of his citizenship. In Yasui v. United States, 320 U.S. 115 (1943), the United States Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of curfews used during World War II when applied to citizens of the United States. Despite a lifetime of effort, Yasui’s case was never reversed.

Attempting another approach to deal with internment, Japanese-American Fred Korematsu challenged the order by arguing that it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the United States Constitution. The Supreme Court’s 1944 opinion (Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)) is now widely regarded as reaching an indefensible outcome, but doing so in a way that ultimately proved to be of great benefit to racial, ethnic, and religious minorities. The court held that a law that discriminated against a racial group was “immediately suspect,” and the law would be unconstitutional unless it could survive “most rigid scrutiny.”

That principle evolved into the so-called “strict scrutiny” standard: laws that discriminate against racial and other minority groups are constitutional only if they are narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling government interest. That level of scrutiny has been called “strict in name, but fatal in fact,” and the number of cases in which a racially discriminatory law has survived can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Unfortunately for Mr. Korematsu, his case was one of them. The Court held in a split opinion that the “Exclusion Act” was, in fact, necessary to promote the compelling interest in national security, and there were no less discriminatory ways to accomplish that objective. Although Korematsu was not overturned by the Supreme Court until 2018, Korematsu’s conviction was vacated by a federal district court in 1984 and, in 1988, Congress enacted a law formally apologizing for the internment camps and providing reparations. “Strict scrutiny” survives as a bulwark of protection against discriminatory government action.

History teaches that grave threats to liberty often come in times of urgency, when constitutional rights seem too extravagant to endure.

Thurgood Marshall, US Supreme Court Justice

Former Japanese-American internees began to return to their old homes in 1945, following the end of the war, and were often met with open hostility by white neighbors. Some found their homes looted and their orchards vandalized, while others endured boycotts of their fruits and vegetables or endured racial slurs and threats. Despite the many instances of blatant racism, intimidation, and hatred, some Oregonians welcomed and supported the returning Japanese Americans.

In 1946 the Oregon State Bar’s Committee on Civil Rights reviewed the progress of the American Civil Liberties Union’s (ACLU) investigation of the federal Justice Department’s mass deportation of Japanese aliens and Japanese-American citizens during the war. The committee recommended that legal action should be taken against the City of Portland’s “after hours” ordinance. That ordinance had given Portland police the right to arrest any person whose explanation did not satisfy them when questioned on the street, which had been Minori Yasui’s “offense.”

In 1946 the Oregon State Bar’s Committee on Civil Rights reviewed the progress of the American Civil Liberties Union’s (ACLU) investigation of the federal Justice Department’s mass deportation of Japanese aliens and Japanese-American citizens during the war. The committee recommended that legal action should be taken against the City of Portland’s “after hours” ordinance. That ordinance had given Portland police the right to arrest any person whose explanation did not satisfy them when questioned on the street, which had been Minori Yasui’s “offense.”

BACKGROUND

In 1922 Takao Ozawa filed for United States citizenship under the Naturalization Act of 1906, which allowed white persons and persons of African descent or African nativity to naturalize. Ozawa was Japanese-American and, though born in Japan, had lived in the United States for 20 years. He attempted to have Japanese people classified as white. The Supreme Court, in Takao Ozawa v. United States, 260 U.S. 178 (1922), a case originating in the Ninth Circuit, found that only Europeans were white and, therefore, the Japanese, by not being European, were not white and instead were members of an “unassimilable race,” lacking status under any Naturalization Act.

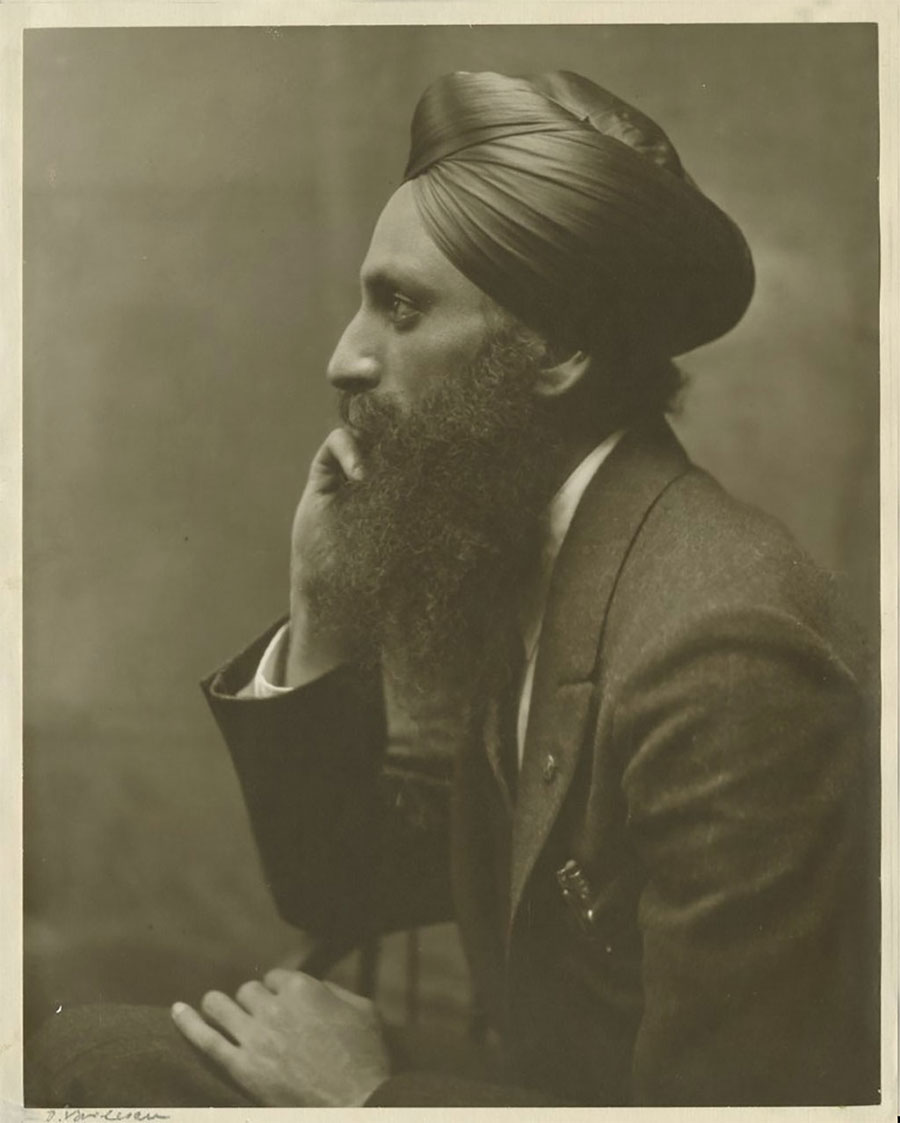

In United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, 261 U.S. 204 (1923), a case originating in Oregon, the Supreme Court decided that Bhagat Singh Thind, an Indian Sikh—who argued that, as a high-caste Indian, he was “Aryan” and, therefore “Caucasian”—was also ineligible for naturalization under the terms of the Naturalization Act of 1906.

Making it further difficult for non-European immigrants to obtain citizenship, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924, which limited the number of immigrants who could be admitted from any country to 2% of the number of people from that country who were already living in the United States in 1890. By granting naturalization only to “any alien being a free white person,” the law was aimed at further restricting the immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans, among them Jews who had migrated in large numbers since the 1890s to escape persecution in Poland and Russia, as well as prohibiting the immigration of Italians, Middle Easterners, East Asians, and Indians.